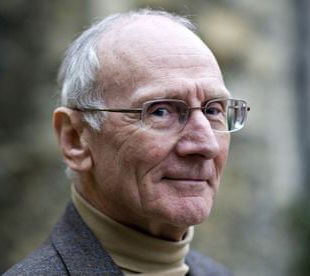

Memories of Professor John Carey

The Daily Telegraph ran an obituary a few days ago of John Carey (1934-25) late Merton Professor of English at Oxford University, that was unsigned - curiously. The usual protocol is surely to sign.

I have many memories of him, as he was my research supervisor while I was an Oxford postgraduate student, writing my doctoral thesis on Thomas Dekker.

I remember that, in his study at Merton College, he had a large set of antique brass see-saw type weighing scales with little weight blocks to adjust them. It symbolized justice and perhaps also the Last Judgement when all shall be "weighed in the balance". For his earnest endeavours to be fair he deserves every credit.

Carey was the last of a generation of academics who could base their reputation on a thorough knowledge of Latin and a "core" of agreed great writers such as Shakespeare, Thackeray and Dickens. He stuck to historicism and biographical criticism and has been proved right as the paths of fashionable critical theory, deconstruction and "gender" have led only to sterile navel-gazing.

His greatest weakness was his complete inability to cope with opening up the canon to include women writers or feminist criticism of those "core" texts.

I attended his postgraduate seminars on Literature and History at Merton for seven years (in the 1980s) and in all that time I think there was only one on the topic of a woman - Lady Anne Clifford, whose inheritance case led to a prolonged legal dispute. To me, in retrospect, that imbalance is a scandal.

The errors in his books usually concern women. He wrote in his book about John Donne (John Donne: Life, Mind and Art) that the lady in Donne's teasing, affectionate poem "To His Mistress Going to Bed" must be a peeress because she is wearing a coronet on her head:

Off with that wiry Coronet and shew

The hairy Diadem which on you doth grow:

Actually, it was merely that Tudor ladies wore wire frames called "head-attires" to support their elaborate hairstyles and hoods.

Many survive in museums, and Shakespeare lodged in the house of a tire-maker in London. "Diadem" is being used in the original ancient Greek sense of simply something wound around the head i.e. a plait of her own hair. The fact that such a ludicrous misreading got through the peer-review unchallenged indicates that the peer-reviewers were as uninterested in the lives of women as Carey was. And this is not just a misreading of one line. It distorts the whole poem from being one about a comfortable sexual intimacy, probably with a wife or wife-soon-to-be, into one about a risky affair with a woman married to the poet's social superior.

His close friends detected a lot of self-portraiture in the book. They thought that in presenting Donne as struggling with the pain of relinquishing Roman Catholicism, Carey was depicting his own struggles with religious belief in an age when it was rapidly going from unfashionable to criminal. He found it more convenient to emphasise his leftwing credentials, the views of a 1950s Labour voter who never agreed with the replacement of grammar schools with comprehensives. The Telegraph reviewer recalls him admiring some aspects of the Thatcher government. I recall him excoriating it.

He wrote about feeling socially excluded when he first arrived at Oxford in the postwar era and claimed that it was still just like Brideshead Revisited, dominated by rich (and idle) public schoolboys. All tosh - in fact, it was never more socially egalitarian, before or since. Women had a hard time getting in, but grammar school boys like A.L. Rowse were Fellows of All Souls, and Richard Burton, a Welsh miner's son, got in on a scholarship. Marxist historian Christopher Hill soon became Master of Balliol.

In his book The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia 1880-1939 (2012) Carey exposed just how widespread fascist ideas and downright genocidal attitudes were in the early 20th century, with Yeats, D.H. Lawrence and many other culprits. These ideas were found in the minds of those of who saw themselves as the most "progressive" (beware such "progressives" today). He concluded that we should read authors such as H.G. Wells and Arnold Bennett. What a pity he never mentioned Rebecca West or G.B. Stern, never considered them as being in the same category as "major novelists" who might be worth studying. Instead he chose Anita Brookner as the contemporary female writer he admired, and defended her from accusations of being "middlebrow" by saying they were made by young male critics who also blamed her for not being South American - a side swipe that reduced them to ridicule. But he's wrong. Plenty of people who are neither young nor male regard Anita Brookner as barely meriting the term middlebrow, and don't care a bit whether she was South American. We were just amazed to hear a Merton Professor of English enthuse, in print and on the radio, over novels that seem to us to be so lightweight they needed to be held down with a brick to stop them blowing away.

Nevetheless, when we look at the state of Oxford nowadays and consider that the title of professor is now conferred on the likes of Stephen Fry, Carey seems to represent a lost age of profound erudition when you had to be fluent in Latin, and familiar with 20 centuries of acknowledged literary classics, to merit those top table dinners of Dover sole, fillet steak and vintage Chambertin.